Leiden: Brill, 2021, 210 p.

ISBN 978-90-04-44099-9

€133,00

Zwolle: Waanders/Haarlem, Teylers Museum, 2023, 247 p.

ISBN 978-94-6262-382-8

€25,95

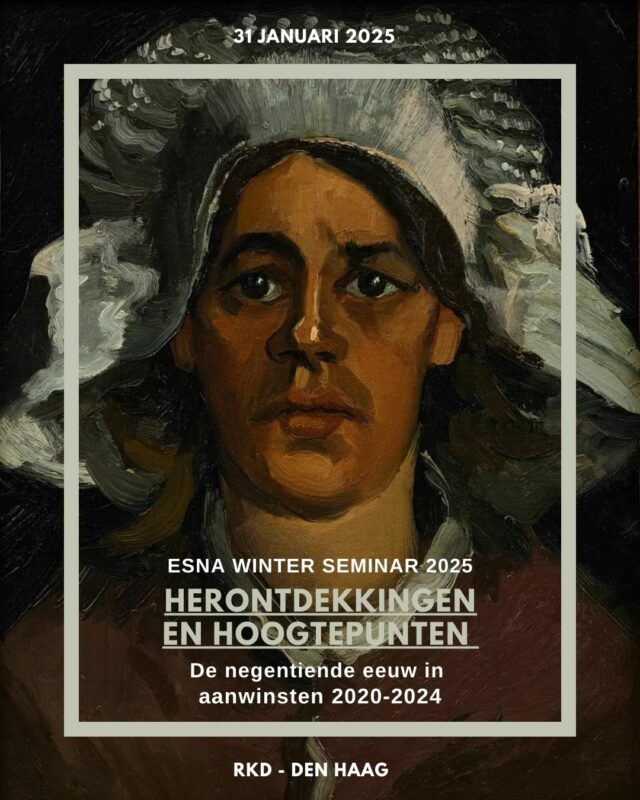

In 1786 schilderde Wybrand Hendriks (1744-1831) een groepsportret van de vijf ‘Directeuren’ van Teylers Stichting, met hun boekhouder/ secretaris rond een tafel zittend. Achter hen stond architect Leendert Viervant (1752-1801) voor een schilderij van zijn twee jaar eerder gereedgekomen ‘Ovale Zaal’, de trots van het huidige Teylers Museum. De vijf bepruikte en bedaagd ogende heren waren de eerste bewindvoerders over de erfenis van Pieter Teyler van der Hulst (1702-1778), die per testament bepaald had dat zijn nalatenschap gebruikt moest worden ter bevordering van godsdienst en wetenschap. Naast deze vijf Directeuren moesten twee genootschappen (‘Collegies’) door het houden van bijeenkomsten en het uitschrijven van prijsvragen zorg dragen voor dat bevorderen van respectievelijk de christelijke godsdienstzin en van natuurwetenschap, dichtkunst, geschiedbeoefening, tekenkunst en penningkunde: Teylers Eerste en Tweede Genootschap. Uit dat beoogde studiecentrum in Teylers voormalige woonhuis (‘Fundatiehuis’) zijn stap voor stap de collecties, de Ovale Zaal en latere aanbouwen van Teylers Museum ontstaan, een ontwikkeling die de erflater zeker niet heeft kunnen voorzien.

De beide hier behandelde publicaties concentreren zich op de eerste decennia van dit proces. Teyler’s Foundation in Haarlem and Its ‘Book and Art Room’ is voortgekomen uit een in 2017 gehouden congres; Wybrand Hendriks is de catalogus bij een tentoonstelling in Teylers Museum in het najaar van 2023. Over het ontstaan en de beginperiode van de stichting zijn al eerder omvangrijke publicaties verschenen: ‘Teyler’ 1778-1978 (Haarlem/Antwerpen 1978), en De idealen van Pieter Teyler. Een erfenis uit de verlichting (Haarlem 2006). In deze nieuwe publicatie wordt onder de loep gelegd wat tot nu toe relatief minder aan bod is gekomen: de inbedding van Teylers Fundatie in het doopsgezinde milieu in Haarlem, en de relatie met sociale en politieke bewegingen in de stad. Wybrand Hendriks, die van 1785 tot 1819 als ‘kastelein’ de zorg droeg voor de tekeningen- en prentencollectie, paste ook daarbinnen maar zijn kunstenaarschap op zichzelf verdient evenzeer aandacht. De eerste (en enige) aan hem gewijde monografische tentoonstelling dateert uit 1972.

In de geschiedschrijving over Teylers Museum was tot nu toe een belangrijke plaats weggelegd voor de natuurwetenschappelijke collecties, en wat de vroege periode betreft vooral voor de verzamelactiviteit van Martinus van Marum (1784-1837), internationaal erkend geleerde en grondlegger van de collecties van fossielen, stenen en wetenschappelijke instrumenten. Onder andere culmineerde dit in twee proefschriften, respectievelijk over Van Marums paleontologische en mineralogische verzamelactiviteit (Bert Sliggers, De verzamelwoede van Martinus van Marum (1750-1837) en de ouderdom van de aarde, Universiteit Leiden 2017) en over de natuurwetenschappelijke collecties (Martin Weiss, Showcasing science. A history of Teylers Museum in the nineteenth century, Amsterdam 2019). In de bundel Teyler’s Foundation in Haarlem daarentegen lijkt men de rol van Van Marum te hebben willen afzwakken. Hij zou bijna 50 jaar lang erg dominant zijn geweest binnen Teylers Tweede Genootschap, waar hij lid van was. Hij manipuleerde het zo dat de onderwerpen voor de jaarlijkse prijsvragen overwegend natuurwetenschappelijk van aard waren terwijl in principe alle aandachtsgebieden van het Tweede Genootschap in aanmerking hadden moeten komen. In de Ovale Zaal, oorspronkelijk bedoeld als bewaarplaats voor boeken, prenten en tekeningen, en als experimenteerruimte voor natuurwetenschappelijke proeven, was nog ruimte over en Van Marum gebruikte dat als argument om zijn verzamelgebieden fors uit te breiden. In 1825 was een eerste uitbreiding noodzakelijk geworden; de instelling evolueerde langzaam maar zeker van centrum voor genootschappelijke wetenschapsbeoefening naar een ook door anderen te bezoeken ‘museum’. Van Marum, die benoemd was als ‘Directeur’ van de verzameling en bibliotheek, voelde zich echter niet geroepen om bezoekers rond te leiden; dat liet hij over aan de kastelein of diens knecht. De eerste kastelein, voorganger van Wybrand Hendriks, zou hij echter zo ongeveer weggepest te hebben. Met Hendriks lijkt de verstandhouding goed te zijn geweest.

Een fundamentele bijstelling van het beeld van het vroege Teylers als startpunt van een lineaire ontwikkeling in natuurwetenschappelijke richting geeft Wijnand Mijnhardt in zijn artikel “The world we have lost’. In praise of a comprehensive concept of science and technology’. Mijnhardt pleit hierin voor een type wetenschapshistoriografie, dat niet uitsluitend uitgaat van een opgaande lijn in de mathematisch gefundeerde natuurwetenschappen. Hij bepleit een meer universele visie, waarin ‘harde’ en ‘zachte’ wetenschappen (de humaniora) een vloeiende overgang vertonen en voorheen ambachtelijke -, technische – en tekenvaardigheden, boekdrukkerijen, ateliers, gilden en rederijkerskamers, kunst- en naturaliakabinetten een belangrijke rol speelden in de ontwikkeling en verbreiding van kennis. Woord en beeld, theoretische en visuele overdracht gingen hand in hand. Een encyclopedisch wetenschapsideaal, dat Mijnhardt ook ten grondslag ziet liggen aan de inrichting van Teylers. Dit zou vooral de achtergrond zijn van de Directeuren van Teylers Stichting, met wie Van Marum dan ook enkele malen in aanvaring kwam.

Die Directeuren, afkomstig uit de stedelijke elite van Haarlem, vertegenwoordigden de band met de encyclopedische wetenschapstraditie. Binnen burgerlijke elites werd wetenschapsbeoefening, in al haar facetten, gezien als vormend voor smaak en verstand, en eventueel praktisch van nut. Ter bevordering daarvan verenigde men zich in genootschappen, al dan niet verbonden aan een verzameling. Haarlem, dat een groot aantal invloedrijke doopsgezinden telde, kende een bloeiende genootschapstraditie. Als zodanig geen toegang hebbend tot openbare bestuursambten, lieten aanzienlijke doopsgezinden zich gelden in het genootschapsleven; ook Pieter Teyler was doopsgezind en Teylers Stichting was een grotendeels doopsgezinde aangelegenheid. In dit verband wijst Eric Jorink, in zijn bijdrage ‘The first museum in the Netherlands?’, op een eerdere naturaliacollectie in Haarlem, die van Levinus Vincent, eveneens doopsgezind. Diens verzameling was net als Teylers Ovale Zaal gehuisvest in een ovale ruimte met koepel – als een tempel verwijzend naar de ordening van Gods Schepping?

Toch wordt in het artikel van Bert Sliggers, ‘How to collect minerals, rocks and fossils for a museum’ (gebaseerd op zijn proefschrift) Martinus van Marum óók gezien als een overgangsfiguur: gedeeltelijk pionier in de natuurkunde, gedeeltelijk generalistisch en encyclopedisch denker. En hij hechtte veel belang aan visuele overdracht, aan het tekenen. In dit verband komt een intensieve samenwerking met Wybrand Hendriks aan bod: deze maakte wetenschappelijke tekeningen van veel van Van Marums collectiestukken. Koenraad Vos, in “Truth to nature’ in the museum? Wybrand Hendriks, Martinus van Marum and the ‘Reasoned Image”, geeft een overzicht en maakt daarbij een onderscheid tussen ‘ideaaltypische’ en ‘realistische’ weergaven; de eerste soort is dominant.

In de catalogus Wybrand Hendriks komen de wetenschappelijke tekeningen alleen kort (om doublures te voorkomen?) aan de orde in het hoofdstuk van Terry van Druten over Hendriks’ beheer van de kunstverzamelingen en zijn diverse andere werkzaamheden voor de Stichting. Een prestigieuze aankoop voor de collectie op zijn advies waren in 1790 ongeveer 1700 voornamelijk Italiaanse tekeningen, oorspronkelijk afkomstig van de een eeuw eerder overleden koningin Christina van Zweden. Studies van Michelangelo, Raphael, Bernini en andere grootheden kwamen zo in de collecties van Teylers Museum. Ook dit wordt in de catalogus vrij kort behandeld, mogelijk omdat er in de bundel Teylers Foundation al een artikel van de hand van Paul Knolle aan is gewijd.

Het eigen werk van Hendriks krijgt alle ruimte. Het grootste deel van het oeuvre bestaat uit landschappen en stadsgezichten, maar er zijn ook getrouwe waterverfkopieën van zeventiende-eeuwse meesters, onder andere van Haarlemse schuttersstukken. Daarnaast kopieerde hij gedeeltes van zeventiende-eeuwse schilderijen en voegde hij deze, al dan niet gecombineerd met andere gekopieerde motieven, in zijn eigen werk in tot nieuwe composities. Mogelijk een vorm van aemulatio. Opvallend zijn de portretten, door Rudi Ekkart en Claire van der Donk betiteld als ‘[o]ntspannen informeel en realistisch scherp’. Naast diverse collega-kunstenaars portretteerde Hendriks doopsgezinde personen en families, bij wie hij, zelf van huis uit niet doopsgezind, via het milieu rond Teylers toegang had. En onder deze doopsgezinden waren er velen die in de roerige decennia aan het eind van de achttiende eeuw betrokken waren bij de patriottenbeweging; de verlichte democratische idealen boden ook aan hen mogelijkheden tot participatie in het stadsbestuur. Zo verkreeg Teylers Stichting, inclusief Wybrand Hendriks, een uitgesproken patriotse signatuur, beschrijft Joost Rosendaal in zijn catalogusbijdrage ‘De Nederlandse revolutie in beeld’. Hendriks, in 1896 gekozen als lid van het nieuwe Haarlemse stadsbestuur, heeft meermalen revolutionaire gebeurtenissen in beeld gebracht, zoals bijvoorbeeld de beëdiging van het nieuwe regeringsreglement in 1787, bij een door Leendert Viervant ontworpen ‘Vrijheidstempel’.

Na 1800 was Hendriks niet meer actief in de politiek. Maar hij bleef gewaardeerd kastelein van Teylers kunstverzameling en een achtenswaardig burger van Haarlem, ook na zijn pensionering. Was door Martinus van Marum Teylers onderdeel van een internationaal netwerk van wetenschappers, dankzij Wybrand Hendriks had het evenzeer uitstraling binnen de Hollandse en vooral Haarlemse verlichte en kunstzinnige burgerij.

De inbreng van Hendriks wordt in beide boeken beslist niet als ondergeschikt aan die van Van Marum gezien. En daarmee wordt ook meer recht gedaan aan het verband tussen kunsten en wetenschappen in de beginjaren van Teylers Stichting.